Iran is experiencing one of the worst water crises in its recent history. Repeated droughts, depleted aquifers, dried-up lakes and rivers, extreme heat waves. The combination of climate change and decades of water policies focused on agricultural self-sufficiency places the country on the brink of what several experts now describe as “water bankruptcy”. This situation affects the economy, social stability, the political legitimacy of the regime, and regional relations.

1. A structurally arid country pushed to climatic limits

Iran is, by its geography, a structurally dry country. More than 80 percent of its territory lies in arid or semi-arid zones, with an average annual rainfall of around 240–250 mm, less than one third of the global average. Two thirds of the country receive less than 250 mm of rain per year, with extremes falling below 50 mm in the central deserts, compared with more than 1,600 mm along the Caspian coast.

Natural vulnerability is reinforced by an unfavourable climatic trend. Iran is expected to experience an average temperature increase of around 2.6 °C in the coming decades, along with an approximate 35 percent decrease in precipitation depending on the region. In practice, this already translates into heat waves regularly exceeding 50 °C, such as in Shabankareh, and into almost five consecutive years of severe drought.

These climatic conditions act as a risk multiplier in a water system already weakened by decades of accumulated management choices.

2. A nationwide water crisis: depleted aquifers, empty dams, vanished lakes

Hydrological indicators converge toward a diagnosis of systemic crisis. Around 76–77 percent of Iran’s aquifer surface is chronically overexploited, with a recharge deficit of around 3.8 mm per year. Groundwater no longer manages to recover, even during more favourable hydrological years.

In half a century, Iran has consumed around 70 percent of its total groundwater reserves, with an annual loss of around 5 billion m³ due to excessive pumping. Over-pumping causes spectacular land subsidence: around Tehran, some areas are reportedly sinking by up to 25 cm per year.

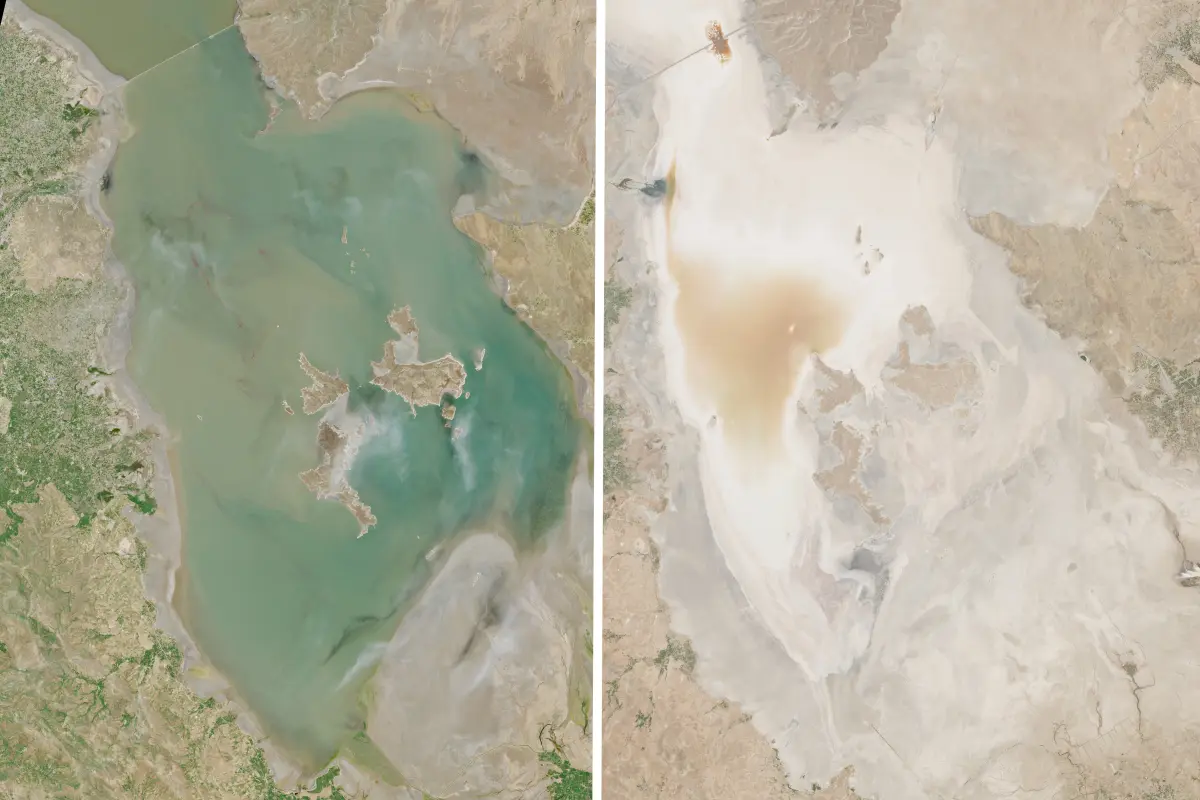

Surface waters follow the same trend. Lake Urmia has lost almost all of its surface area in just a few decades. Many other lakes and wetlands, such as the Hamoun marshes, have met a similar fate, generating dust and salt storms.

In 2025, several major dams supplying Tehran reached exceptionally low levels, triggering prolonged cuts and urgent calls to reduce consumption, with scenarios even mentioning the partial evacuation of the capital.

3. Agriculture, dams and self-sufficiency: the weight of political choices

The core of the crisis is political and structural. Since before 1979 and even more so after the Revolution, the Iranian state has made food self-sufficiency a strategic objective, reinforced by sanctions and the desire to reduce imports.

This has meant a rapid expansion of irrigated areas, massive support for highly water-consuming crops (wheat, rice, sugar beet, orchard fruits), and the construction of hundreds of dams and diversions to supply them.

Approximately 90 percent of water consumed in Iran is now used by agriculture, often through inefficient irrigation systems. Thousands of legal and illegal wells have worsened groundwater overexploitation.

This model rests on an implicit socio-economic compromise: in a context of sanctions and limited growth, agriculture absorbs a significant share of rural employment. Any abrupt reduction in water allocations faces strong social and institutional resistance.

4. Droughts turning into social crisis and protest

Between 2018 and 2023, several waves of protest erupted around water. In 2021, Khuzestan was the centre of the “uprising of the thirsty”, fuelled by drought and salinity. Protests spread to other provinces, with discourse linking water shortages and criticism of governance.

In marginalised regions such as Sistan-Baluchestan or Kurdish areas, access to water highlights inequalities: ageing infrastructure, villages not connected to networks, dependence on irregular tanker trucks.

Daily impacts are clear: declining agricultural yields, rural exodus, community tensions around canals, increased water costs for urban households.

The water crisis is now perceived as a structural risk factor for internal stability.

5. Environmental and health effects: dust, salinity, ecosystem loss

Dried wetlands become sources of dust and salt storms, degrading air quality and respiratory health. Salinisation is advancing in many agricultural plains, causing desertification and loss of arable land.

The combination of drought, heat and pollution heightens health risks: respiratory diseases, cardiovascular issues, heat strokes. The erosion of biodiversity and degradation of ecosystem services reduce the country’s resilience.

6. A question of national security and regional relations

Iran is involved in several transboundary river basins. On the Helmand, the 1973 treaty guaranteeing a minimum flow is contested during drought periods, aggravated by recent Afghan dams and the absence of robust enforcement mechanisms.

To the west, major Turkish dams on the Euphrates and Tigris reduce flows toward Iraq and certain already fragile Iranian areas, intensifying dust storms and agricultural degradation.

Drought becomes a national security issue: internally for social stability, externally for diplomacy with Kabul, Ankara, and Baghdad.

7. What possible trajectories? Between constrained adaptation and risks of deadlock

Scenario 1: continuation of reactive measures, relying on emergency steps, inter-basin transfers, deeper wells, water cuts. No treatment of structural causes. Risk of gradual worsening.

Scenario 2: revision of usage, with reduced cultivated areas, conversion to less water-intensive crops, more efficient irrigation, well closures. Implies rural restructuring and social support.

Scenario 3: emphasis on regional cooperation through transboundary agreements, joint risk management, hydraulic and energy interconnections. Depends on regional power balances and financing, limited by sanctions.

8. Why Iran’s drought is a major issue to watch

The crisis exposes the limits of a model based on the continuous expansion of water uses in a structurally arid country. It acts as a test of the state's ability to revise its priorities in the face of non-negotiable ecological constraints.

Iran concentrates several typical regional factors: arid climate, high population, agricultural dependence, transboundary basins. Its management of water transition offers a laboratory for understanding the Middle East’s water futures.

The political and social dimension makes it a central issue. Water structures relations between centre and periphery, cities and rural areas, state and citizens. Repeated droughts place the water question at the heart of debates on territorial justice, political legitimacy, and the hierarchy of national priorities.

Sources

- ClimaHealth – Investigation of climate change in Iran

- AIRE / Malekinezhad et al. – Average rainfall 251 mm, 90% arid/semi-arid

- Atlantic Council – Climate profile: Iran

- The Guardian – Iranians asked to limit water use as temperatures hit 50°C

- Nature – Anthropogenic drought dominates groundwater depletion in Iran

- Wikipedia – Water scarcity in Iran

- The Guardian – How drought and overextraction have run Iran dry

- The Washington Post – Taps are running dry in Iran

- Al Jazeera – As the dams feeding Tehran run dry

- Wikipedia – 2021 Iranian water protests

- freeiransn – Iran’s Water Insecurity: How Policy and Politics Deepened the National Crisis

- futureuae – A Nexus of Environmental, Political, and Security Challenges

- ocerints – Economic and social impacts of water scarcity in Iran

- PMC – Climate change and health in Iran: narrative review

- Wikipedia – Afghanistan–Iran water dispute

- Global Voices – Ilisu Dam and regional dust storms

- SpecialEurasia – Water Scarcity in Iran and Strategic Consequences

- PMC – Decline in Iran’s groundwater recharge

- Carnegie Endowment – Iran’s Water Crisis Is a Warning to Other Countries

- IFRC – Iran Drought 2021 Summary

- Wiley – Iran’s Agriculture in the Anthropocene

- ScienceDirect – Ensemble-based projection of future hydro-climatic extremes in Iran