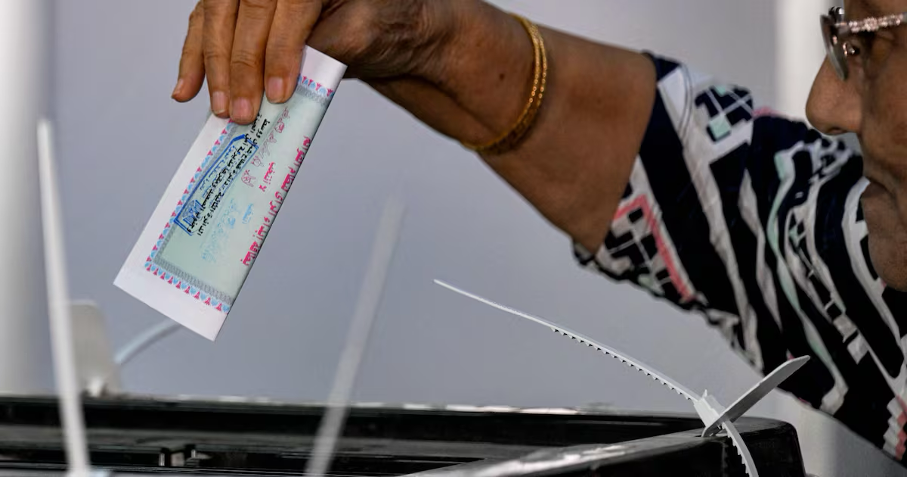

Ballot.

Egypt: Controlled Ballots, Same Political Score - The Second Senate Election

Cairo wakes up in the humid August heat as loudspeakers in the streets urge passers-by to do their "national duty". The second Senate election, created in 2019, takes place over two days and concerns more than sixty-three million registered voters spread across more than eight thousand polling stations. The ritual is supervised by 9,500 judges, according to the National Election Authority, which guarantees a ballot that the State presents as proof of calm pluralism. Yet behind the institutional vocabulary, the political scene appears frozen. There is a single National List for Egypt bringing together thirteen parties closely aligned with the presidency, competing for the hundred seats allocated by proportional representation, while most of the 428 declared individual candidates carry the same majority colours. The dominance of the Future of the Nation party (Mostaqbal Watan) is clear, reinforced by satellite formations from the old Wafd liberal party and small socio-conservative blocs now under the presidential banner. This is a sign of enforced consensus rather than genuine competition.

The electoral system itself tells the story. Two hundred seats are up for election, one hundred by closed list, one hundred by first-past-the-post. The president then appoints the final third directly. The Senate is a consultative body only, reviewing bills and constitutional amendments before they reach the more powerful House of Representatives. This structure recalls the Shoura Council, dissolved in 2014, then revived five years later, supposedly to widen political participation. Paradoxically, the return of this consultative chamber has gone hand-in-hand with the expansion of presidential powers allowed by the 2019 constitutional reforms. These changes permit Abdel Fattah El Sisi to stay in office until 2030, while tightening military control over civilian life.

The first Senate election in August 2020 already gave a taste of this unanimity. The official turnout was 14.23%, less than nine million voters. The Future of the Nation list won a third of the list seats without contest and almost all individual seats in the two following rounds. Five years later, the electoral landscape has shrunk even further. The Authority now counts an electorate of nearly sixty-nine million thanks to updated registers, but political choice has narrowed. Only one group dominates the proportional vote, while the opposition, fragmented, sometimes competes in single-member districts through independent personalities. The new Senate is likely to be as monochrome as the previous one, if not more so. The single list only needs five percent of those registered to be declared victorious, a mere formality given the logistical resources mobilised by governors, rural notables and state-backed media.

This absence of real competition is visible in the streets. Posters cover the façades but only show a colourful mosaic of faces backing the same line, often prominent businessmen or media personalities from the outgoing parliament. Female presence, maintained by the ten percent constitutional quota, remains confined to lists where eligible places are carefully allocated. The aim is less to convince than to display a united society. The government multiplies reminder SMS, governors set up misting fans and tents near schools, and free municipal buses bring voters to the polls. Participation becomes a civic performance. Any figure higher than 2020 will be presented as a success. Early reports mention notably high female turnout in Delta and Upper Egypt governorates, a phenomenon highlighted by state media.

To understand this institutional inertia, the elections must be placed in a tough economic context. Runaway inflation since the 2022 monetary crisis keeps driving up the cost of essentials and fuel. Queues at subsidised bakeries are longer, the currency has lost more than half its value in three years, and a diffuse exasperation is heard in downtown cafés. The government repeats that stability depends on continuity of reforms and that the Senate will provide a chamber for reflection on development plans. However, the lack of credible checks and balances feeds a sense that debate is tightly controlled. Social protest remains sporadic, quickly suppressed by strengthened security since the end of the state of emergency, which has been replaced by permanent anti-terror laws. The long twilight of the 2011 revolutionary movements finds its symbolic end here.

Abroad, 136 polling stations in 117 countries welcomed the diaspora two days earlier. Diplomacy coordinated the logistics by video and reported "enthusiastic participation". The ballot boxes travelled to Cairo under diplomatic seal for inclusion in the national count. The event takes on an identity dimension. Official narrative celebrates the "new Republic" uniting nationals and expatriates, while human rights groups remind us that part of the opposition lives in exile, often under judicial pressure, deprived of passports or prosecuted for spreading "false news".

The question of the Senate goes beyond simple partisan control. It sheds light on the regime's method of consolidation, described by several researchers as "renovated authoritarianism": a mix of pluralist façade and economic centralisation, where major business leaders close to power gain political visibility and access to public contracts. This deal is visible in electoral lists packed with construction and steel tycoons. This capitalism of influence feeds criticism of governance, where the parliamentary agenda is barely distinct from the priorities of the Cabinet and sovereign agencies, leaving little space for social mediation or independent legislative initiative.

Still, popular legitimacy is seen as essential. Hence the ceremonial investment in the vote, and live coverage of the president casting his ballot at his old Heliopolis school, meant to seal the image of a renewed national pact. The prime minister, governors, the grand mufti, all appear on screen, urging the crowds, praising the devotion of electoral staff. Three deaths from heart attacks on the first day are cited as proof of civic commitment. State media, backed by strict laws against "fake news", echo only the official version. Private TV channels linked to security holdings reinforce the same line, while online spaces are filtered, with some opposition sites still blocked in the country.

The real turnout will therefore be the figure most scrutinised by observers. In 2020, abstention reached a record level. This time, the government hopes to break the twenty percent barrier, a modest but politically vital aim, as the autumn will see the launch of the campaign for the House of Representatives, whose budgetary and legislative powers matter more. Analysts note that the Senate serves as a full-scale test, both for measuring local machine discipline and for testing health security protocols, which remain crucial due to recurring seasonal epidemics. If there are any real fault lines, they may appear then, as internal negotiations within the ruling coalition focus on the allocation of future parliamentary lists, a more strategic issue than the Senate for regional power-brokers.

On the diplomatic front, Cairo uses the election to project the image of a stable state, a key partner on Israel-Palestine and Libya. This stability is praised by many foreign governments, who prioritise security cooperation and migration control. The lack of visible political alternatives becomes acceptable in exchange for regional guarantees. However, this diplomatic truce does not silence criticism from international organisations about prolonged detention without trial or restrictions on union rights, topics almost absent from parliamentary tribunes due to the lack of elected representatives to champion them.

Domestically, economic priorities focus on renegotiating an IMF financing programme, reviving tourism damaged by regional crises, and constructing major infrastructure around the new administrative capital. The Senate will be expected to approve these flagship projects, presented as engines of growth, while also rubber-stamping tax hikes or new electricity tariffs, socially explosive issues that are absent from the colourful electoral billboards promising prosperity and social protection.

In the streets of Bab El Louk, scented with jasmine in the evening, political talk mixes with the honking of tuk-tuks. Everyone knows the ballot boxes will not change the Nile’s course, but the river has a long memory. In the golden light on Fatimid façades, people share a joke or a sigh and sometimes the stubborn hope that one day, speech will recover the clear tone of genuine debate, because in Egypt, even millennia-old stones end up speaking if given silence.